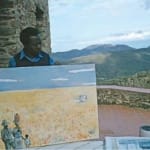

Peter Clarke holds up his gouache 'A far journey' (painted in Norway) while visiting George Hallett at Mas Domingo, near the village of Boule d'Amont, in the south of France, spring 1979. (Photograph: George Hallett)

Peter Clarke holds up his gouache 'A far journey' (painted in Norway) while visiting George Hallett at Mas Domingo, near the village of Boule d'Amont, in the south of France, spring 1979. (Photograph: George Hallett)

Peter Clarke South African, 1929-2014

By his late forties, Clarke’s single-minded commitment to an art career began to pay off and he started to be rewarded with recognition and increasing opportunities. However, in a perverse twist of fate, the constraints on opportunities he had suffered from under apartheid law, now re-emerged in the form of the international boycott placed on South Africa by the global community, consequently restricting opportunities for artists to take advantage of international contacts and circumstances. Despite this, Clarke applied to work on printmaking at the Graphic Workshop at Atelier Nord in Oslo, Norway. Unfortunately, in light of the international boycott, his application was declined. However, despite the rejection he continued to apply, and his persistence paid off. Two years after his initial application he was invited to work at Atelier Nord from October 1978 to the end of January 1979. It is from this time that the current painting emanates.

Once in Norway, Clarke found that distance seemed to bring events at home closer to him. As he said he: ‘looked back to South Africa, as though being away made me more aware’.

In the seminal publication on the artist Listening to Distant Thunder, authors Philippa Hobbs and Elizabeth Rankin discuss this painting and the context of its creation in some detail:

“Other works made in Norway referred to South Africa alone. The title of one of these, A far journey (1978), was a response to his feelings of unfamiliarity in Norway: ‘…it was getting very cold and the Arctic was pressing on me’. The stippled ochre surface of the landscape conjured up the hot dry spaces of Africa that stretch endlessly to distant horizons. For the artist it brought back special memories of travelling through the Karoo in the summer. But, like other gouaches made at the time, this work was more than just an expression of dislocation from home. Taking advantage of his roomier living space and access to large sheets of rag paper, Clarke scaled up his landscape to panoramic proportions handled with fluid painterly surfaces. And not only was the scale bigger and the paintwork freer, but he took the experimental leap of using strips of paper collage instead of brushstrokes for the streaks of cloud in the sky and other elements.

“A far journey accompanied him on a springtime visit on his way home from Norway to his old friend George Hallett, in exile since 1970 and now living at Boule d’Amont, near Perpignan in the south of France. Hallett’s recollection of this encounter remains vivid, perhaps because of the volume of photographs he took of the artist, who was to become, Hallett considers, his most extensively documented male subject. The two men worked through an ‘inspirational period’ of experiment, Hallett enjoying that quality about an artist that ‘inspired one to take pictures’ (Hallett interview 2007). One of these photographs has a particularly poignant relationship to the works Clarke had been making in Oslo. Hallett’s camera captured him holding up A far journey, thus juxtaposing the expansive Cape Flats image and the mountainous Pyrenean backdrop behind him, visually linking familiar home territory with present location. Distance afforded Clarke a more detached perception.”

Hobbs, P. and Rankin, E. (2011). Listening to Distant Thunder: The Art of Peter Clarke. Cape Town: Fernwood Press. p.144