William Kentridge: Three Early Drawings

-

William Kentridge circa 1987

© Image courtesy Kentridge Studio

-

Sir Sydney and Lady Felicia Kentridge

Sir Sydney and Lady Felicia Kentridge© Image courtesy South African Jewish Museum Archives

-

Irene Geffen

© Image courtesy South African Jewish Museum Archives

-

William Kentridge, A Formal Portrait of the Young Man as an Artist, 1980

William Kentridge, A Formal Portrait of the Young Man as an Artist, 1980 -

-

A Formal Portrait of the Young Man as an Artist, signed and dated 17 November 1980, seems to capture Kentridge’s uncertainty at this point in his career. The embossed mark of Irene Geffen’s Notary stamp recalls the possibility of his pursuing a career in law but everything else in the drawing revolves around conflicting definitions of art. The drawing is a mock-heroic self-portrait with the artist seated in the left centre, his body facing the front while he turns his head and shoulders to the right in the direction of the voluminous curtains such as were used in formal portraits in the Baroque era. Other indications of the European tradition of grand-style portraiture are the table on the left with a classical urn containing flowers (possibly arum lilies); and, in the right centre near a fragment of classical architecture, a study of a hand like those made by Renaissance artists seeking the appropriate grand gesture for their subjects.

-

All these details are summarised in the inscription at the bottom right centre, 'A Formal Portrait of the Young Man as an Artist'. There is no confirmation from the time that this was the actual title of the drawing but, with no other evidence available it certainly seems captures its purpose. The inscription, of course, is an inversion of the title of James Joyce’s first novel, ‘A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man’ except that Kentridge has introduced the word ‘Formal’ seemingly to capture both the grand-style aspects of his drawing – and the pretensions of his claims to be an artist. Kentridge had worked with an imagined historical Joyce in the Junction Avenue Theatre’s production of Tom Stoppard’s Travesties in November 1978. While preparing to go to Paris, he must have felt some identification with Joyce’s hero Stephen Dedalus, self-evidently a projection of the author, who at the end of the novel finally leaves Dublin for Paris to devote himself to art.

-

-

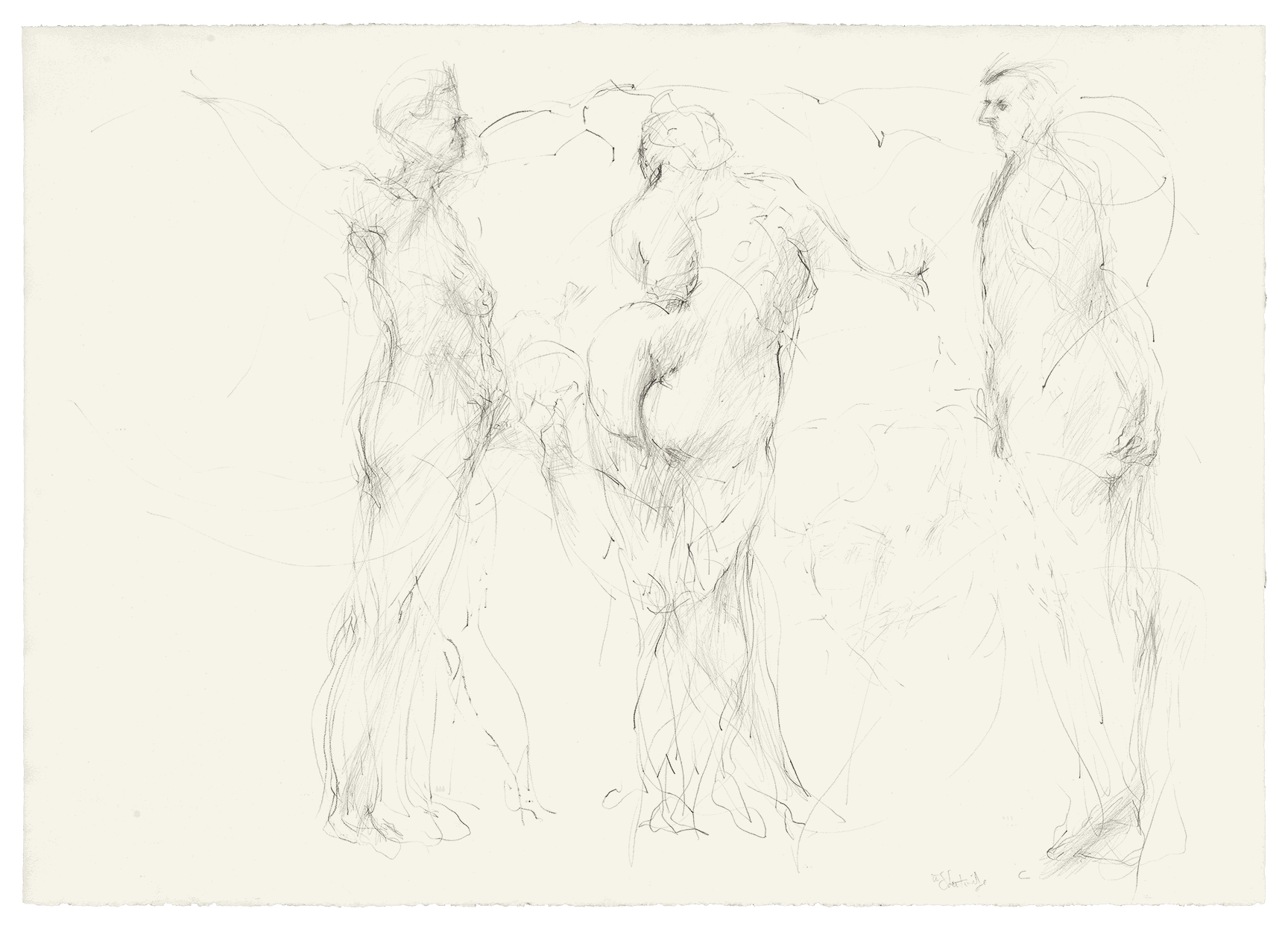

William Kentridge, Untitled (Three figure studies)

William Kentridge, Untitled (Three figure studies) -

-

The list of drawings shown at Kentridge's second Market Gallery exhibition may or may not be complete and may even be not entirely reliable. Thus the drawing listed as 'Seated Man Being served by a Standing Companion' might relate to the 'Formal Portrait' discussed above, despite the omission of the second figure of the title. But 'Lunch in the Garden' aptly describes the third drawing of the present group to which we will turn in a moment. However, it would be a stretch to connect the undated drawing of three nudes to either the 'Birth of Venus' (which had also been shown on the first Market Gallery exhibition) or 'A White Annunciation 1' or 'Woman and Lamp', or 'A Circus'. But these titles do seem to connect Kentridge's project at this time with European Art History which is certainly reflected in the style of the 'Three Nudes'.

-

In 1980, the nude was decidedly out of favour in the South African academy and so Kentridge's use of it is significant. His composition recalls the design of Renaissance 'Judgement(s) of Paris' or 'The Three Graces' and the style of the three figures suggests reference to artists such as Titian or Rubens. But, as in the 'Formal Portrait', this tradition seems to be invoked only to be parodied: the precise central placement of the principal woman's buttocks constitutes an improbable punctum that precludes any possible moral purpose; and the detail of the man on the right scratching his buttocks transforms the heroic potential of Renaissance history painting from the sublime to the ridiculous. On the eve of his departure for Paris, Kentridge clearly had a deeply ambivalent relationship with European Art History.

-

-

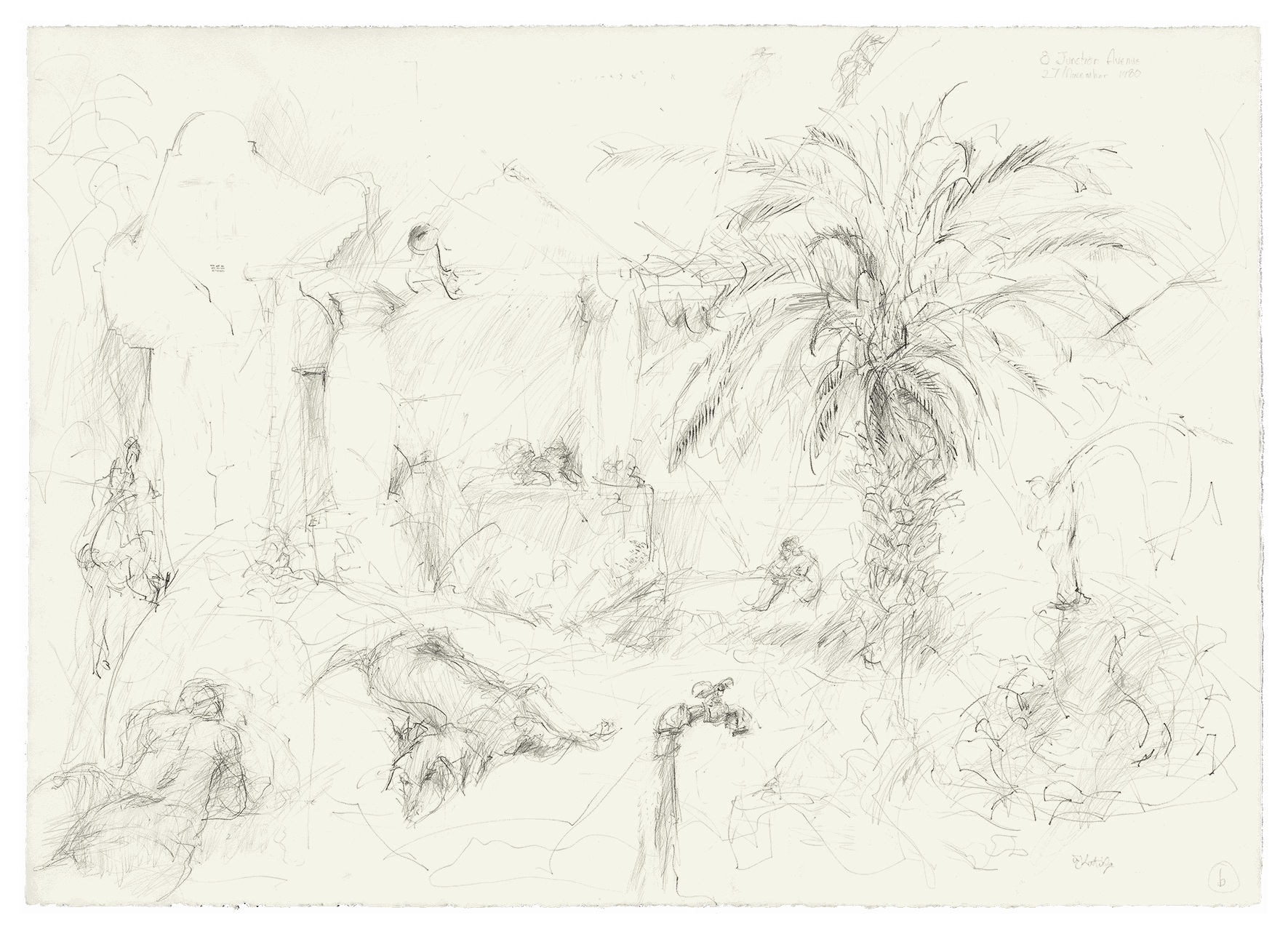

William Kentridge, Lunch in the Garden, 1980

William Kentridge, Lunch in the Garden, 1980 -

-

Lunch in the Garden, signed and dated 27 November 1980, also connects with the European tradition recalling in both title and feel the ‘Dejeuner sur l’Herbe’ of Giorgione and Manet, and the ‘Fetes Champetres’ of Watteau and others. The drawing is inscribed ‘8 Junction Avenue’ which Kentridge, in a personal communication, confirmed was the address of a student commune where he stayed with his wife Anne Stanwix - and the rest of the Theatre Company - for a time before leaving for Paris. The commune comprised a series of cottages around a shared garden. Bill Ainslie is reported to have encouraged his students at the Johannesburg Art Foundation to draw in their gardens.

-

The drawing features a palm tree; a colonnade with a table set for lunch; a rockery; various figures relaxing; a garden tap; and the commune’s dog (‘Doggie’), sleeping – altogether a veritable suburban ‘Fete Champetre’. But the changes in scale, and of viewpoint, between these discreet incidents determine that Kentridge has composed this scene, not with conventional Renaissance perspective, but with what he described later as the “completely arbitrary and changeable” nature of filmic space, an experience he had learned in the few films he made before 1980. “The freedom that came from being able to play with space” was to underpin all his subsequent ‘Drawings for Projection’ – in fact his entire narrative output.

-

-

Artworks

-

Words by Prof. Michael Godby

References:

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, William Kentridge, Brussels: Societes des Expositions du Palais des Beaux-Arts de Brussels, 1998.

Email communication from William Kentridge and Anne McIlleron, 31 May 2024.

Email communication from Steven Sack, 18 June 2024. Steven Sack was a founder member of the Junction Avenue Theatre Company and resident at the Park Town commune.