Walter Battiss: The Irrepressible Nudist

-

Walter Battiss, Female nude

Walter Battiss, Female nude -

Three Female Nudes

-

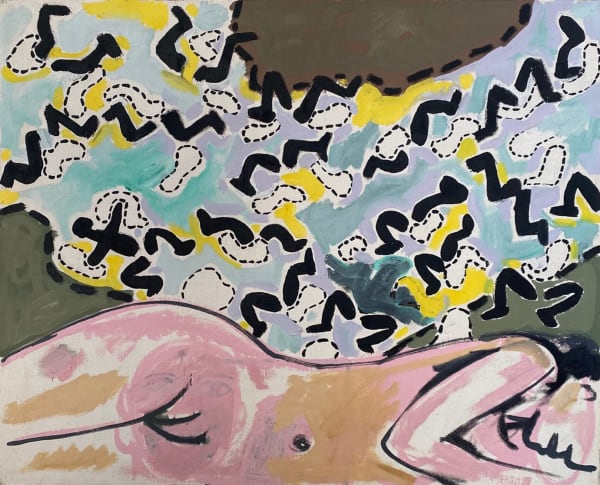

From the early 1970s onwards, Battiss’ pursuit of paradise assumed a tropical tone, with the artist travelling extensively in the Pacific and Indian Oceans throughout that decade. These three paintings—Female nude, Woman sunbathing, and Woman by a river—are characteristic of Battiss’ late style and most likely belong among the island works that populated that period. Seen alongside one another, they extend a comparative study of Battiss’ stylistic agility.

While all three women are described with fluid brushstrokes in pronounced outline, cast no

-

shadow, and are without depth, they offer distinctly different variations on the same theme. Battiss rarely painted portraits; his figures are more often ideals that are lent a human likeness. They are archetypes rather than individuals.

As such, the images are not lascivious or sexualised but, rather, the artist seems to delight in the interplay of colour and form. Such are these three women, their compositional lightness is that of a mature artist and confident colourist. -

Battiss’ art knowledge was vast, and he was intimately familiar with the historic genre of the female nude which he plays with so effectively in these compositions. Loaded as they are with the weight of thousands of years of human creative development, we understand the first traces of depictions of female nudity to emanate from the 6th century BC, portrayed in everyday scenes painted on ceramic vessels. This is a trope that begins in ancient Greece, where sculptors paid homage to the gods by representing them in idealised human form.

-

-

Walter Battiss, Woman sunbathing

Walter Battiss, Woman sunbathing -

Walter Battiss, Woman by a river

Walter Battiss, Woman by a river -

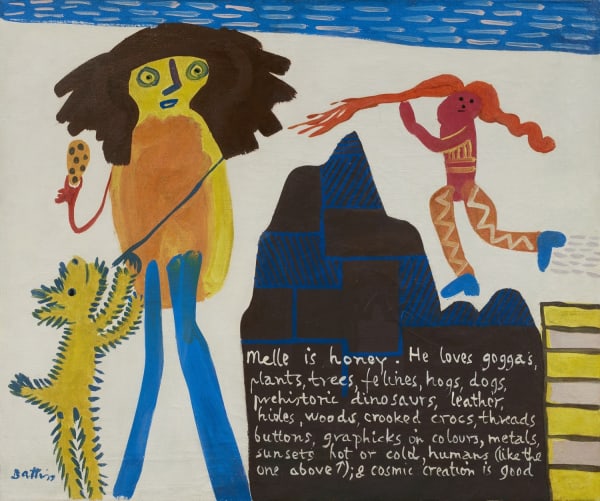

Melle is honey...

Walter Battiss, Melle is honey…, c.1975

Walter Battiss, Melle is honey…, c.1975 -

Fervently childlike in its wide-eyed, candid style, Melle is honey... communicates the artist’s enchantment with the natural world and interconnectedness with other species, biological systems, processes and phenomena.

The dog is off the leash and the hair of the two characters flows untamed and wild. In a familiar gesture of interspecies subjectivity, the dog is about to be given a treat. The spirit of loving reciprocity brought into play by the three figures is amplified by the textual statement written into the rock, concluding with the words ‘cosmic creation is good’.

The combination of figures and text within the same frame evidence the artist’s deep and abiding interest in the relationship of visual sign to verbal meaning and his study of the calligraphic detail of Arabic script, alphabets, hieroglyphic forms and pictographs.

Battiss became interested in archaeology and rock art as a young boy when his family moved from Somerset East in the Karoo to Koffiefontein, a small farming town in the Free State, in 1917. A family friend accompanied him to see ‘the ancient stones’ and this early experience of indigenous art would have a lifelong influence on his work as an artist.In form and content, this painting is realisation of that desire. With its simplified figures and absence of depth, it is an high-spirited pop rendering of the reduced shapes and non-receding perspectival plain of rock art.

-

'When I came down from the mountains I was articulate and free. For I had conversed with the white rocks and the lilac trees, the coucal and rhebuk… The twisted rivers and the endless veld spoke of animate and inanimate space. All this was my peculiar discovery but I had no desire to paint an anecdote about them, but rather to make pictures of them in such a way that I exposed the happy change they had worked within me.'

–Walter Battiss

-

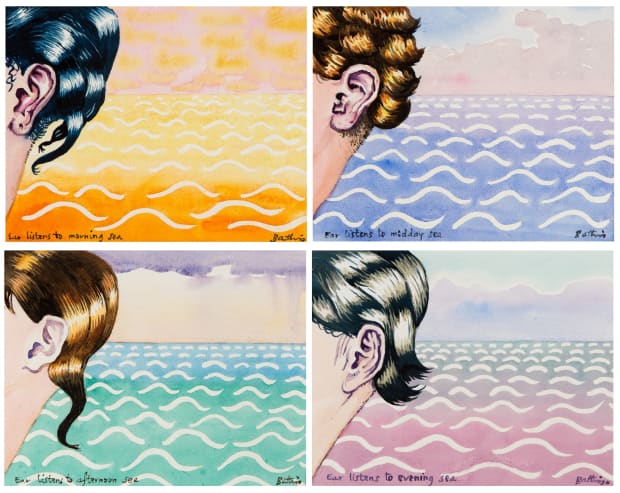

Mrs Thomas Leisure Bay

Walter Battiss, Mrs Thomas Leisure Bay - Ear listens to morning, midday, afternoon and evening sea (quadriptych)

-

Artworks

-

Words by Lucienne Bestall and Dr. Alexandra Dodd

Sources:

Scully. L. (1963). Walter Battiss. University of Pretoria: Unpublished thesis. p.18

Carman, J. and Isaac, S. (eds). (2005). Walter Battiss: Gentle Anarchist. Johannesburg: Standard Bank Gallery.

Sampson, L. (2015). 'Eccentric artist Walter Battiss is back with a bang'. Sunday Times. 10 May. Available online.Battiss, W. (1979). Walter Battiss by Walter Battiss. Dawidow, D. and Eager, M. (eds). Produced by documents of South African Art in cooperation with Fook Mountain Press. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand

O'Toole, S. (2017). 'Battiss in Johannesburg'. adjective. 1(1): pp.9-12Battiss, W. 'Fragments of Africa,' in Carman, J. and Isaac, S. (eds). (2005). Walter Battiss: Gentle Anarchist. Johannesburg: Standard Bank Gallery. p.88.

'Walter Battiss (1902-1982)', NLA Design and Visual Arts, 2013. Available online.'Walter Battiss', South African History Online, 2017. Available online.