Ephraim Ngatane: Still life with vessels and newspaper, 1964

-

-

Ephraim Ngatane was born in Lesotho and raised from the age of five in Soweto. He was a student at the Polly Street Art Centre from 1952-54 where he studied painting under Cecil Skotnes. He subsequently became a teacher at the Jubilee Art Centre, with his contemporary Durant Sihlali, when Polly Street closed down.

In 1955, he joined the Weekend Painters group, which was originally initiated by his colleague Sihlali, and included the likes of Sydney Kumalo. In these workshops the participating members were free to explore more naturalistic and documentary approaches to their work than the relatively docile attitudes promoted in formal teaching environments. In this process, Ngatane developed a distinctively painterly and psychologising approach to his art where an unmistakably realist tenor came to characterise his work, which was concerned with a politically charged documentary realism.

-

He was acknowledged for his uncompromising concern with the gritty and atmospheric representation of the lived experience of black South Africans in the context of the time, and this was his influence and legacy on his contemporaries which included Dumile Feni and Louis Maqhubela. Ngatane rejected the primitivizing effects of Expressionism and, in response, he doggedly pursued the values and truths inherent in social and domestic realism. This stood him apart from the stylistic and conceptual mainstream of his colleagues and contemporaries in the Polly Street and Jubilee Art Centre environments.

Ngatane is one of the best known and most celebrated artists emanating from the period when the first professional black African artists emerged through the Polly Street Art Centre in the 1950s. These artists were concerned with the social conditions of their segregated communities, and so emerged the genre of social domestic realism, as developed a generation before by the great masters of early South African Black Modernism, George Pemba and Gerard Sekoto.

-

-

-

Ephraim Ngatane, Still life with vessels and newspaper, 1964 (in situ)

Ephraim Ngatane, Still life with vessels and newspaper, 1964 (in situ) -

Ephraim Ngatane was mostly concerned with documenting township life in his paintings. He drew from his experience in, and memories of, shantytowns and township life – the crowded living conditions and domestic scenes, transportation, work and labour, sport and leisure activities, and other memorable events such as the two occasions it snowed in Soweto in the 1960s. He was deeply motivated by his conviction to record the living conditions and lived experiences of his people, and so would go to wherever people were experiencing the realities of this life, such a forced eviction and relocations, or inflicted disasters, to record events.

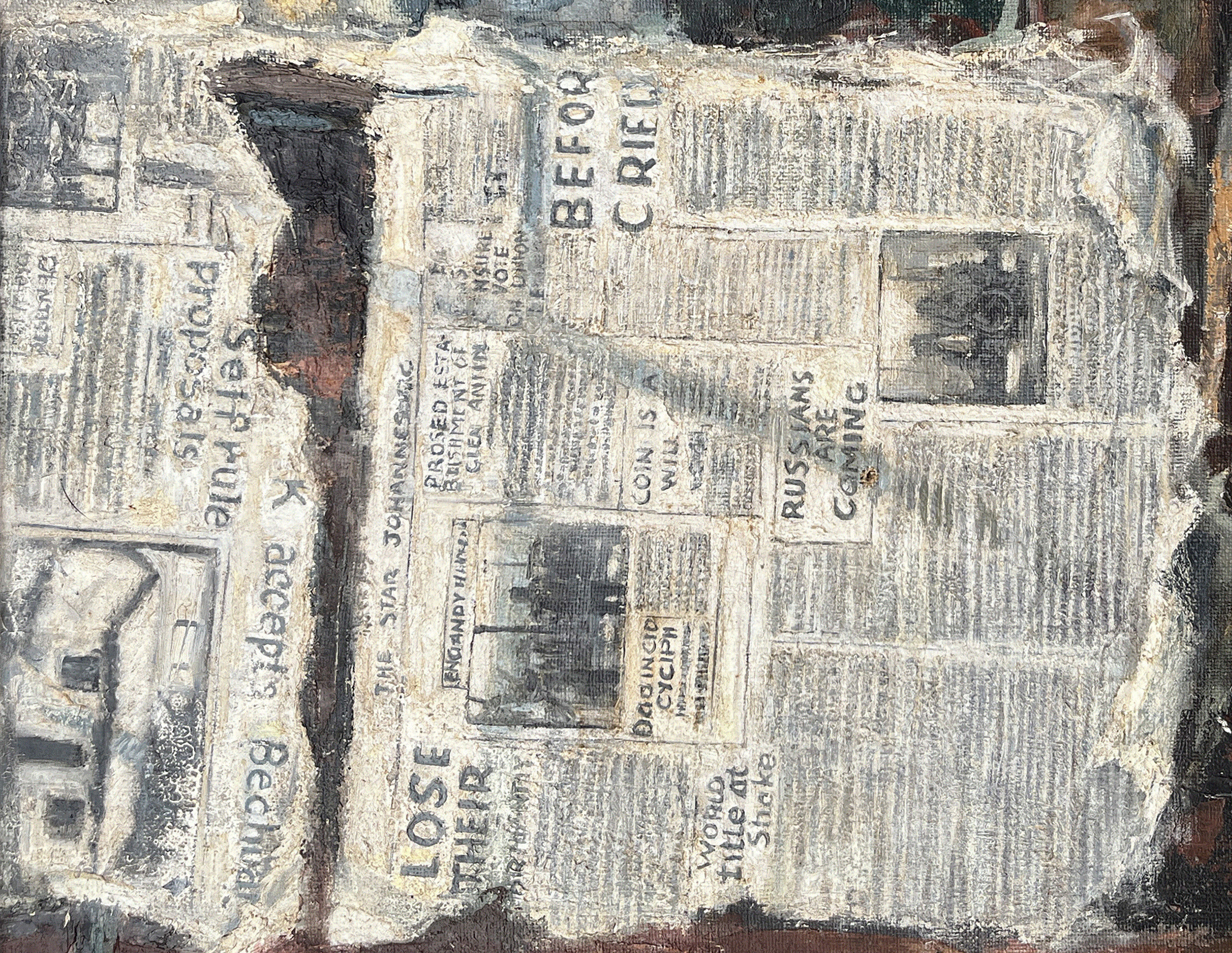

While his work focused on documenting the politically charged everyday realities of black life under apartheid, he did not make work that was overtly political or critical of the incumbent regime, for fear of being arrested, jailed, or worse. In this painting, Still life with vessels and newspaper, 1966, he ostensibly depicts a benign still life scene with pots and vessels on a low table covered in newspaper – a harmless and congenial portrayal of daily life. However, through closer inspection a deeper reading of the subject emerges in the form of a critique of the social conditions and injustices of his lived experience.

During the 1960s, the implementation of apartheid and the repression of internal opposition continued despite growing world criticism of South Africa's racially discriminatory policies and police violence. Hundreds of thousands of Black, Coloured, and Asian people were forcibly removed from certain areas to land that was demarcated for these racial groups.

-

Ephraim Ngatane, Still life with vessels and newspaper, 1964

Ephraim Ngatane, Still life with vessels and newspaper, 1964 -

These were dark times in South Africa in general, and especially for the black population. It was a time characterised by increasing doubt, despair and desperation amongst the community that formed the majority of the populace. Internationally, it was the height of the Cold War between Russia and the USA, when the communist threat dominated news headlines in the West.

Ngatane and his intellectual contemporaries were well aware of these conditions and, consequently, would have been deeply cautious of the South African Security Police, the so-called Special Branch, which was a unit of the South African Police during apartheid which was synonymous with abductions and disappearances. He and his contemporaries would not risk open criticism of the incumbent regime while it was at the height of its strength. In a daring and courageous way, unseen in most of his paintings, Ngatane subtly takes aim at the vast social injustices that prevailed at the time, as borne in the newspaper headlines of The Star Johannesburg depicted in this painting.

Cautious not to make his comments too legible or literal, he takes care to obscure the more politically oriented headlines. More legible lines include RUSSIANS ARE COMING. A clear reference to the tensions of the Cold War, but more subtly to the opportunism of the incumbent Nationalist regime in South Africa in using this tension to justify and legitimate their own agenda of suppression by referring to any enemies of their policy as Communists, and creating laws for the eradication and punishment thereof, to protect their unjustifiable and increasingly precarious position.

The line BEFORE CRIED is clear and bold, though the following text is unclear, leaving the viewer to draw their own interpretations based on the slew of social miscarriages happening at the time.

Another line, PROPOSED ESTABLISHMENT OF… could refer to The Bantu Administration Minister, M.C. Botha, who announced measures leading to the creation of a second “homeland” in the Northern Transvaal. The ten homelands that were ultimately created were: Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Ciskei, Venda, Gazankulu, KaNgwane, KwaNdebele, KwaZulu, Lebowa, and QwaQwa.

-

Ephraim Ngatane, Still life with vessels and newspaper, 1964 (detail)

Ephraim Ngatane, Still life with vessels and newspaper, 1964 (detail) -

Another obscured headline reads: …***k accepts Bechuan… Selfrule proposals. This probably refers to The Bechuanaland Protectorate, a controlled state established on 31 March 1885 in Southern Africa by the colonising United Kingdom, which subsequently became the Republic of Botswana on 30 September 1966. In June 1964, the United Kingdom accepted proposals for a democratic self-government in Botswana. Subsequently an independence conference was held in London in February 1966 and the seat of government was moved from South Africa to the newly established Gaborone. Based on the 1965 constitution, the country held its first general elections under universal suffrage and gained independence on 30 September 1966. Self-governance was the ultimate goal for the black majority of South African citizens.

Another legible headline is: LOSE THEIR, followed by a much more obscured “Authority” or “Identity” which is difficult to decipher. This could refer to any one of the numerous pieces of legislation that was developed under the Suppression of Communism and Criminal Procedure Amendment Acts referred to above.

Ngatane was acutely aware of, and deeply affected by, the political turmoil happening at the time in his home country. His desire to make his position clear and to utilise his platform as a visual artist to address these political and social injustices is unmistakeable. However, at the same time, his fear of, and unwillingness to, risk attracting the attention of the Special Branch is tangible. This resulted in muted allusions to various prevailing conditions that highlighted the tyranny and unjustness of his lived experience, which is made more poignant through his own redaction and self-censorship.

Coupled with this, is the fact that this is a still life painting, which is rare in his oeuvre. This is further compounded by the fact that this painting is on canvas. The combination of these facts makes this an incredibly unique painting by Ngatane. Being very poor throughout his short life, opportunities to paint on expensive canvas were few and far between. Consequently, when such opportunities did come along, it stands to reason that he would have reserved his best work, best materials, and his most valuable and significant subject matter when creating the resulting artwork.