John Koenakeefe Mohl: Riders in the Snow, Lesotho

-

-

John Koenakeefe Mohl’s Riders in the Snow, Lesotho invites you into an evocative encounter with the artist’s vision of rural life in southern Africa – landscapes of snow-clad mountains, stoic Basotho riders wrapped in blankets, and the quiet drama of journeys through harsh terrain. A key figure of the Sophiatown Renaissance, Mohl was deeply committed to portraying the dignity, resilience, and everyday beauty of Black South Africans. This work, likely painted in the early 1960s, stands as both a lyrical celebration of natural splendour and a subtle commentary on escape, place, and identity in the face of apartheid’s divisions.

-

-

John Koenakeefe Mohl1903-1985Riders in the Snow, Lesothosigned and inscribed 'in the 20th century'oil on canvas laid down on board85 x 92.5 x 5.5 cm (including frame)

John Koenakeefe Mohl1903-1985Riders in the Snow, Lesothosigned and inscribed 'in the 20th century'oil on canvas laid down on board85 x 92.5 x 5.5 cm (including frame)

42 x 54.5 cm (excluding frame) -

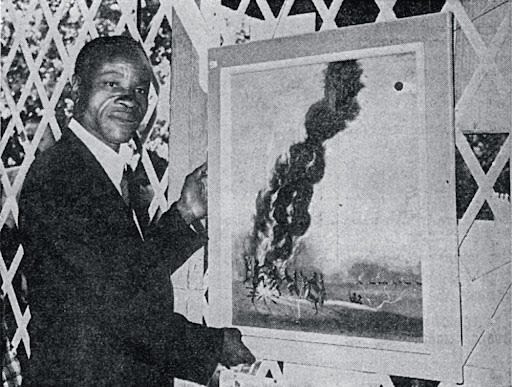

John Mohl holding one of his paintings

John Mohl holding one of his paintings -

The influence of the Weimar Republic, modernism, and Bauhaus on Mohl's life and work has often been questioned and is seemingly conspicuous by its absence. But although the connection with the abstract work of Paul Klee's might at first not be apparent, Prof Neil Parsons writes, 'Mohl and Klee's paintings share values of graded colour and light seen in bright open air or under an urban industrial gloom.' (Parsons, p.97) Mohl's work also shares with Klee the appearance of small schematic figures. However, the Kunstakademie in Dusseldorf was most famous for its tradition of landscape painters, and here there is a clear influence.

Mohl certainly did not talk of his art practice in Klee's terms of painting being the expression of a transcendental world. Mohl, as the various surviving interviews with him reveal, was gripped by the beauty of the South African landscape outside the horrors of apartheid. But he was also concerned with the expression of a culturally specific world and the need for black artists to reveal their lived experience through art. As he told the famous sociologist Prof. Tim Couzens, 'South Africa ... needs artists ... to paint our people, our life, our way of living, not speaking in the spirit of apartheid or submission.' (Dolby) This was a sentiment that foreshadowed the Black Consciousness philosophy of Steve Biko. As Biko memorably proclaimed:

More, has to be revealed, and stress has to be laid on the successful nation-building attempts by people like Shaka, Moshoeshoe, and Hintsa. These are areas calling for intense research work to provide some desperately-needed missing link. It would be too naive of us to expect our conquerors to write unbiased histories about us anyway. (Biko)

These were similar terms to the ones Mohl spoke of when, interviewed two decades earlier in the 1950s by Bantu World, he stated:

-

A very high percentage of our talent lies buried. It is for Africans themselves to unearth it, train it and enable it to make its full contribution to the culture of our country. What is more, African artists will be among the foremost interpreters of our people to other races. (Miles, p.62)

-

-

Paul Klee, Landschaft mit dem Galgen (Landscape with Gallows), 1919

(Image courtesy Mutual Art)

-

Laurence Stephen Lowry, A Factory Town under Snow, 1942

(Image courtesy Mutual Art)

-

-

According to Elza Miles and Parsons, Mohl was commissioned 'to record scenes of historical importance' by Tshekedi Khama, the king-regent of the Tswana people in Bechuanaland (now Botswana). Mohl, however, was never politically active in the South African resistance movements, preferring to remain an educator and exhibit his work to as broad a public as he could. After the apartheid state demolished his White Studio, he founded the group 'Artists Under the Sun'. As Parsons explains, the group 'held weekend exhibitions in the open air on the railings of Joubert Park, defiantly placed outside the Johannesburg Art Gallery.' (Parsons, p.91)

Mohl's work has often been interpreted as 'realist depictions' of South African life. Despite having studied in the Weimar Republic in the modernist heyday of Paul Klee, Max Beckmann and George Grosz, most art historians have not seen a significant thematic or representative connection. Parsons for one argues that Mohl's work has far more in common with that of the English working-class painter L.S. Lowry. However, this is to overlook the Neue Sachlichkeit (or New Objectivity) realist movement of the Weimar period, and as James Malpas puts it, their 'sardonic reflections on street-life and social turpitude.' (Malpas, p.35)During the 1940s, his landscapes were exhibited regularly at the very same Johannesburg Art Gallery - an institution that was for all intents and purposes closed to him after 1948 and the rise of the apartheid government. His only known solo exhibition was at Trevor Huddleston's Church of Christ the King in Sophiatown in the late 1950s, shortly before the forced removals and the deconsecrating of the church.

During Mohl's years in Sophiatown, we know that he was painting scenes of Bechuanaland. Several of these paintings have survived, and often depict figures in the mist crossing the border from South Africa into Bechuanaland. The personal significance of these works for a man who was a Batswana, living in a racially divided South Africa, would have been clear. Again, Parsons explains, Mohl 'found some kind of fulfilment by crossing [even if only in his imagination] the frontier into the Bechaunaland Protectorate, an unconquered African civilisation by comparison with the Union of South Africa.' (Parsons, p.99)

People crossing the frontier and escaping the racial oppression of apartheid South Africa was seemingly an inherent aspect of these pictorial odysseys. As Parsons goes on to add, in the 1960s, 'Lesotho became Mohl's alternative landscapes between mountains populated by horsemen in colourful blankets and women carrying water on their heads.' (Parsons, p.106)

Certainly what both Lowry and Mohl had in common with these Weimar modernists, is that their paintings contain this movement's magic-realist sensibility. As Lowry said of his own work: 'most of my land and townscape is composite. Made up; part real and part imaginary ... They just crop up on their own, like things do in dreams.'

Mohl's work too has the very same, part-real/part-dreamlike qualities of which 'Riders in the Snow' is a perfect example. Painted almost certainly in the early 1960s, 'Riders in the Snow' was produced at the time of some of South Africa's most desperate moments. It was a period of mass arrests, massacres such as Sharpeville, brutal state oppression and the trials and banning of all political dissidents. -

-

With this in mind, it could well be argued that the work is an image of not only rural life, but of an escape from the realities of apartheid into a mystical mountainous world. In the background are the turreted peeks of the Drakensberg, once the home of the philosopher-king Moshoeshoe. The sun stands tiptoe on the misty mountain tops, illuminating the Basotho riders wrapped in their iconic blankets, their conical hats bobbing to the horses' trot, the women burdened with their bundles of firewood.

The leafless snow-covered tree, with its skeletal-like branches and trunk, intimates a bleak and unforgiving reality. The snow-packed mountains testify that this is 'just the worst time of year for a journey'. And yet the painting, with the dappled colours of the human figures heading to the village, offers a sense of a return to rustic arcadia. The playfully distorted gangling figures raised in subtle impasto stand out, as in so many of Mohl's work, as everyday victims and masters of their circumstances and environment.

Mohl's significance both as an artist and educator has often been underestimated. He was by nature a quiet man with an understated politics. His almost unique representations of South Africa and the black rural and working class peoples have regularly been overlooked due to what may seem like a uncommitted political stance. But this belies the fact that Mohl was not only a consummate artist, influenced directly by some of the most important art movements of the 20th century, but was a dedicated South African who chose a less travelled path in his political expression.

-

-

John Koenakeefe Mohl, Horsemen through the Snow in Lesotho

Sold for R167,100 (Johannesburg, 2009)

-

John Koenakeefe Mohl, Daybreak, After Snow Falling, 1964

Sold for R182,080 (Johannesburg, 2020)

-

John Koenakeefe Mohl, Back from Work in Snow, 1981

sold for R220,000 (Cape Town, 2018)

-

-

[John] Mohl’s art records the changes that took place in southern Africa during the 20th century. It is a testament of life as he experienced it. He painted both rural and urban life with equal devotion. The stretches of open, unpolluted space in his landscapes are in stark contrast to the grey smoky air of his Witwatersrand scene.

Hayden Proud, curator emeritus of historical collections at the Iziko South African National Gallery