Dumile Feni: The Early Drawings and Sketches of a Great African Modernist

-

Dumile Feni, 1971

Dumile Feni, 1971 -

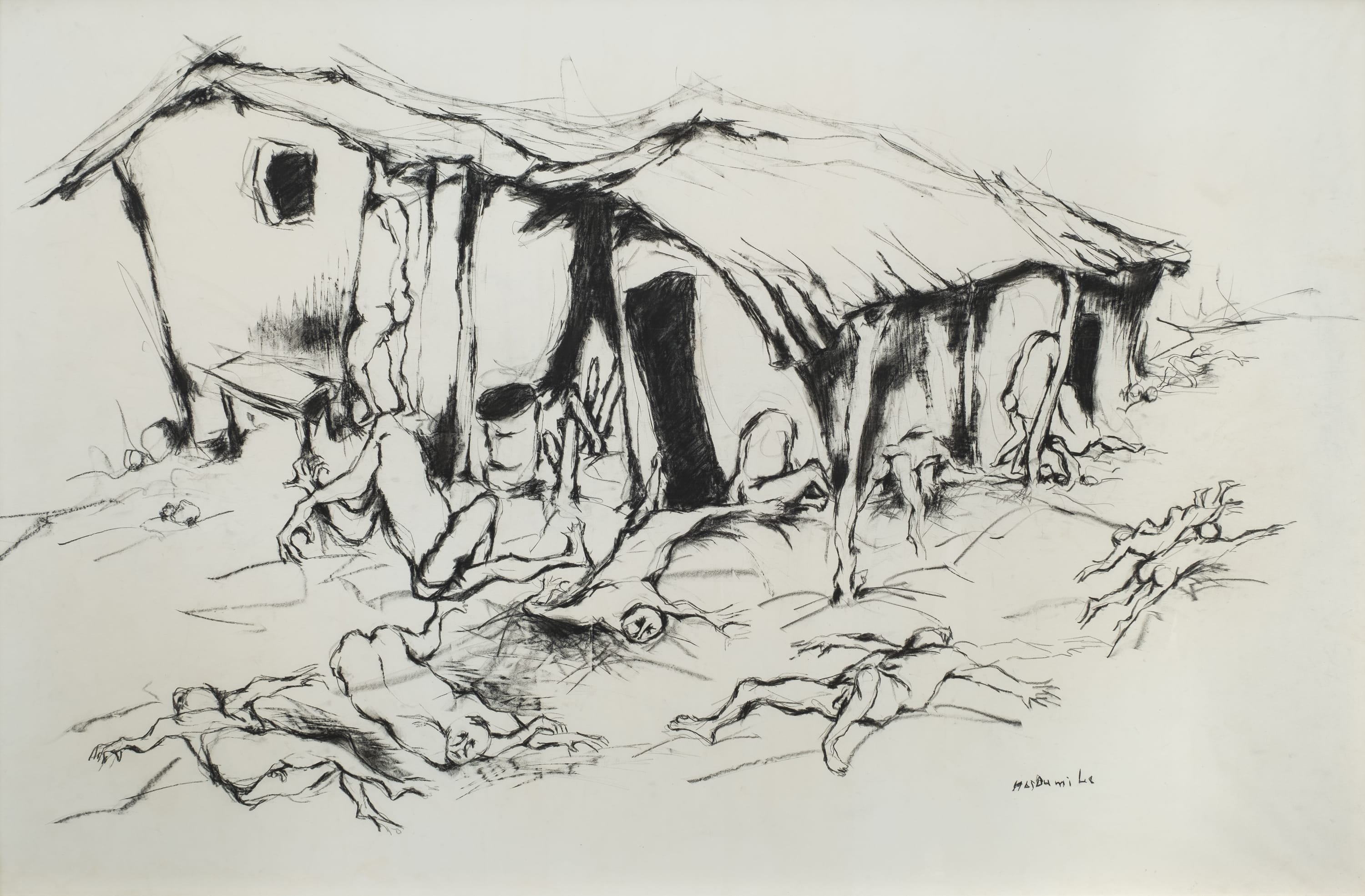

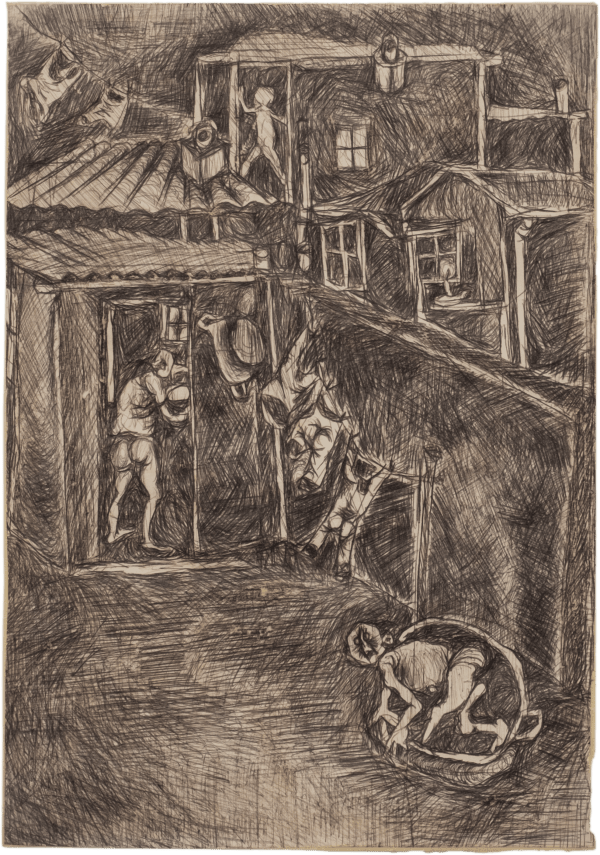

Stricken Household, 1965

Stricken Household, 1965 -

Wash Day, Douglas Lane, Durban, 1966/7

-

Dumile’s artistic vision and influence are perhaps like no other South African’s. As the prominent American curator, Dan Cameron puts it, William Kentridge’s ‘brand of expressionism can be directly tied to the intense large charcoal drawings and small ink drawings of the artist Dumile, with whom he studied.’

-

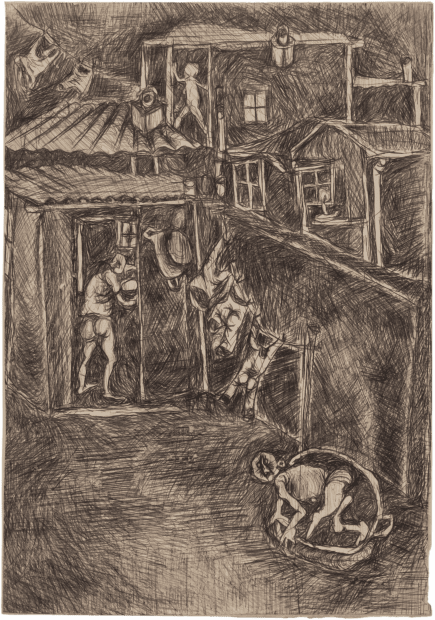

Feud, 1966/7

Feud, 1966/7 -

‘Dumile took the raw material of his life in Soweto — and it was a life of raw ordeal — and translated it into work in a manner which revealed a capacity to face unflinchingly the most frightening extremities of human desperation and cruelty, without spilling over into sentimentality or overblown expressionism.’

Prof. Anitra Nettleton

-

Early Figure Studies

-

Untitled (Seated woman), c.1966

-

Artist Contemplating Suicide, c.1966

-

Untitled (Young boy with arms stretched out), 1966

-

-

'Dumile extended the expressive distortion of the human form to its imaginative limit.'

Prof. John Peffer

Prof. John Peffer, raises the temperature in his praise, writing that Dumile ‘extended the expressive distortion of the human form to its imaginative limit.’ This practice, it could be argued, began with two seminal works, Stricken Household (1965) and Wash Day Douglas Lane (1966-67).These, together with the drawing Untitled (Young boy with arms stretched out), 1966, are key moments in Dumile’s development. The motif of Untitled (Young boy with arms stretched out), of a figure with hands outstretched, would appear in many of his works, sometimes as domestic workers hanging clothes on a line, at other times, as figures in a state of abject crisis. This drawing demonstrates the skill for which Dumile was so venerated. An image with a quality of representation and foreshortening that few of his contemporaries could match.

The importance of these works lies not only in the development of Dumile’s expressive line and distinctive mark-making, but in the themes that would haunt his life: the ravages of apartheid and the indignity of those held in domestic servitude. Stricken Household (1965) is one of the first works where Dumile’s use of line and expressive, distorted modelling of bodies is clear. Lines and expressiveness that would become the distinctive elements of his oeuvre.

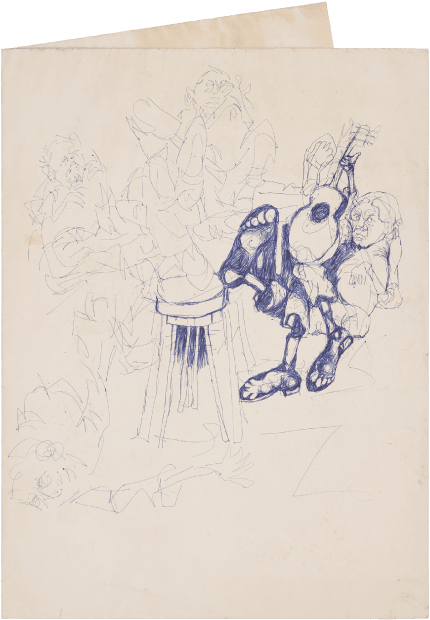

As Badsha explained, while Dumile lived with him, his attention was often absorbed watching women at work in domestic settings. Washer women at their troughs or washing lines, and women burdened with children gripped him. And he often began to sketch their domestic toils out on quotidian paper. These drawings are crowded with tensile and anxiety-ridden lines that rake across the paper, producing the contorted forms of women at labour.

-

-

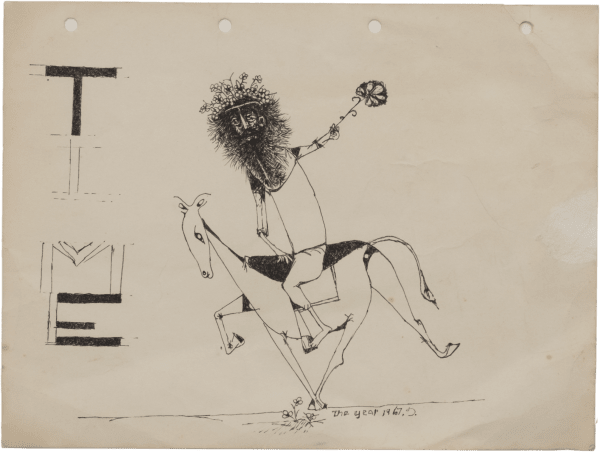

Time (The year), 1967

-

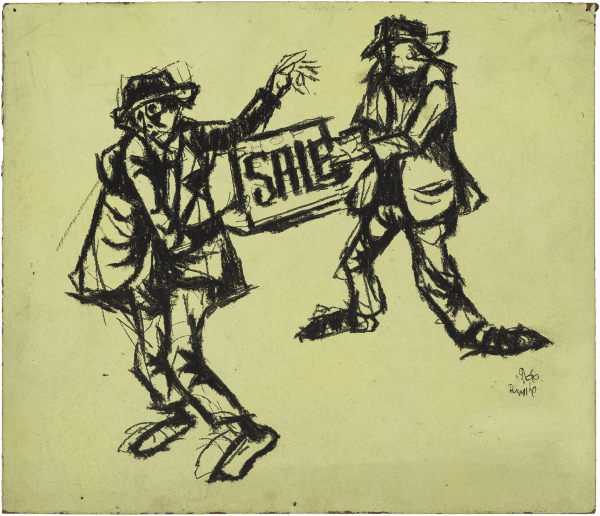

SALE, 1966

-

-

From the early stages of his career, he was referred to as the 'Goya of the township'

There is, however, also a ludic playfulness in many of Dumile’s early works that was part of the almost tireless energy of which many of his friends and acquaintances talk. Time (The Year) (1967) and Feud (1966/7) foreshadow work such as Kentridge’s Nose on Rearing Horse II (2007). However, what is, in historical terms, of equal significance is Dumile’s unflinching representation of apartheid South Africa and his vision of apartheid-era dystopia.

What set Dumile apart from many of his artist friends was his urge to represent South African apartheid realities. As John Peffer writes in Art and the End of Apartheid, ‘until the 1970s, there were few paintings or prints by black artists... or overt images of protest.’ Dumile (almost exclusively, along with perhaps Albert Adams) was a distinct exception. Peffer goes on to say, ‘Dumile’s bizarre figures confronted the effects of authoritarian abuses of power in a novel way, and his outspoken critique of racialism made him stand out from his contemporaries.’

From the early stages of his career, he was referred to as the ‘Goya of the township’. And much like Goya, who worked in the Rococo tradition but was driven to new forms and subjects by his violent circumstances and illness, Dumile too was influenced by his circumstances and the very real terrors of TB and apartheid. As Badsha revealed to us, Dumile’s sense of mortality and of looming asphyxiating death was an ominous existential reality in his day-to-day experience. And this frenetic need to hold onto the vestiges of life while living under the oppressions of apartheid created an anxiety which must have been overwhelming, and is clearly apparent in his work.

-

Musicians, c.1966

Musicians, c.1966 -

-

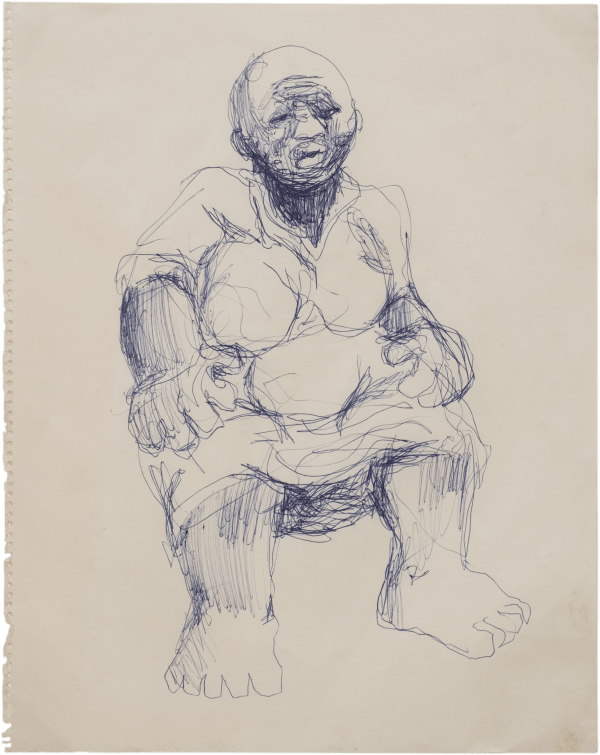

Untitled (Portrait of Docrat), 1968

-

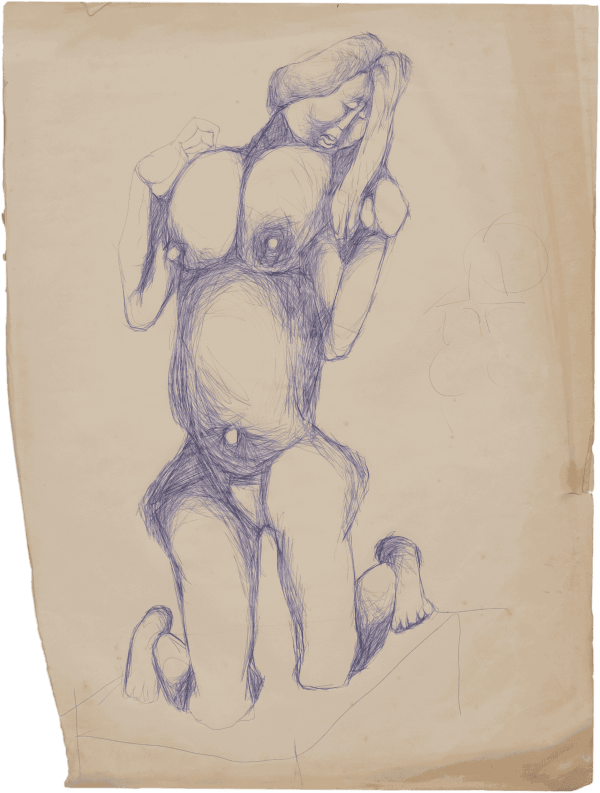

Untitled (Kneeling woman), 1966/7

-

-

Venice Biennale 2024

The 60th Venice Biennale in 2024 featured an overview of African and diasporic perspectives. Curator Adriano Pedrosa invited 331 artists and collectives to show their work under the title Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere. The majority of the participants of which emanate from the Global South. His selection included Dumile Feni.

The sketch of Docrat (1968), along with the larger, more finished Untitled (Kneeling woman), 1966/7 of a kneeling naked woman, prefigures the elongated, mask-like style of his later drawings and sculptures.

The sketch of Docrat bares many of the structural facial lines and modelled features of the sculpture selected by Adriano Pedrosa for his exhibition ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ at the Venice Biennale.

-

-

Adriano Pedrosa, curator of the 2024 Venice Biennale

-

Dumile Feni sculpture included in the exhibition 'Foreigners Everywhere', at the 2024 Venice Bienanle, curated by Pedrosa

-

The 60th International Art Exhibition, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, from Saturday 20 April - Sunday 24 November at the Giardini and Arsenale venues

-

-

This remarkable collection of early sketches and drawings has all of the motifs, suggestions, and large works of an artist who has been rightly venerated as one of Africa's greatest.'

Dr. Matthew Blackman

-

Available Works